Security Lab researchers uncover how online advertising can be used to track individuals

(Cross-posted from Allen School News.)

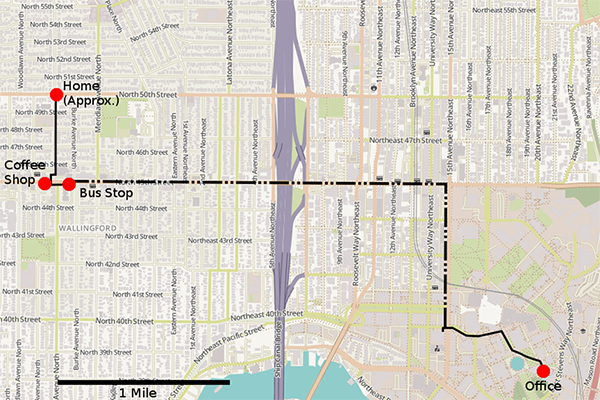

This map, representing an individual’s morning commute, shows the locations where the research team was able to track the person’s movements through location-based ads.

Online ads may not only be trying to sell you something; they may be selling you out. That’s according to a team of researchers in the Allen School’s Security and Privacy Research Lab, who recently discovered how easy it is for someone with less than honorable intentions to turn online ads into a surveillance tool. They found that, for as little as $1,000, a person or organization could conceivably purchase ads that will enable them to track someone’s location and app use via their mobile phone — gaining access to potentially sensitive personal information about that individual’s dating preferences, health, religious and political affiliation, and more. The team hopes that by sharing its findings publicly, it will raise awareness among online advertisers, mobile service providers, and customers about a potential new cybersecurity threat.

This threat stems from how the existing online advertising ecosystem enables ad purchasers to precisely target consumers based on their geographic location, interests, and browsing history for marketing purposes. The problem, as researchers explained in a UW News release, is that the same infrastructure can be exploited by people and organizations other than advertisers to precisely target individuals in ways that could compromise their privacy and security. According to former Allen School Ph.D. student Paul Vines, lead author on the project, it would be easy for anyone from a foreign agent to a jealous spouse to sign up with an online advertising service and track another individual.

“If you want to make the point that advertising networks should be more concerned with privacy, the boogeyman you usually pull out is that big corporations know so much about you. But people don’t really care about that,” Vines explained in a Wired article about the project. “[T]he potential person using this information isn’t some large corporation motivated by profits and constrained by potential lawsuits. It can be a person with relatively small amounts of money and very different motives.”

As the team discovered, online advertising can deliver fairly detailed information about a person’s behavior. For example, the researchers were able to determine an individual user’s location within a distance of 8 meters based on where their ads were being served. By establishing a grid of hyperlocal ads, the team was able to discern an individual’s daily routine based on where ads were served to the user’s device at various points along the way.

The team refers to this method of information gathering as ADINT, or “advertising intelligence,” reminiscent of well-known intelligence collection tactics such as SIGINT (signals intelligence) and HUMINT (human intelligence). To test the capabilities of ADINT, Vines and his coauthors — Allen School professors Franziska Roesner and Tadayoshi Kohno — purchased a series of ads through a demand-side provider, or DSP, which is an entity that facilitates the purchase and delivery of targeted advertising. They set up their ads to target a mix of 10 actual users and 10 facsimile users with the help of each device’s unique mobile advertising identifier (MAID), which functions as a sort of “whole device” tracking cookie. The team then repurposed the tools designed to deliver relevant ads for commercial purposes to instead collect information on each user’s whereabouts and behavior.

The ADINT research team, from left: Tadayoshi Kohno, Franziska Roesner, and Paul Vines Dennis Wise/University of Washington

Movement was not the only thing they could track; it turns out that ad purchasers have the ability to learn a lot about a person by viewing what apps they use, including popular dating and fitness-tracking apps. The team’s experiments also revealed that the individual being tracked does not need to actually click on an ad in order for ADINT to work, because purchasers can see where the ad is being served regardless of whether the target interacts with it.

“To be very honest, I was shocked at how effective this was,” said Kohno, who co-directs the Allen School’s Security and Privacy Research Lab with Roesner. “There’s a fundamental tension that as advertisers become more capable of targeting and tracking people to deliver better ads, there’s also the opportunity for adversaries to begin exploiting that additional precision.”

The team surmises that ADINT attacks could be driven by a variety of motives, from criminal intent, to political ideology, to financial profit. According to Roesner, the ease with which the team was able to deploy targeted ads against individuals calls for heightened awareness and vigilance — not just within the computer security community, but on the part of the policy and regulatory communities, as well.

“We are sharing our discoveries so that advertising networks can try to detect and mitigate these types of attacks,” she explained, “and so that there can be a broad public discussion about how we as a society might try to prevent them.”

The team will present its findings at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society taking place in Dallas, Texas later this month.

To learn more about ADINT, visit the project website here. Read the UW News release here and the Wired feature here, and check out additional coverage by The Verge, Mashable, and Mic.